Who is at risk for having malrotation?

Who is at risk for having malrotation?

Malrotation occurs equally in boys and girls. However, more boys have symptoms by the first month of life than girls.

Why is intestinal malrotation a concern?

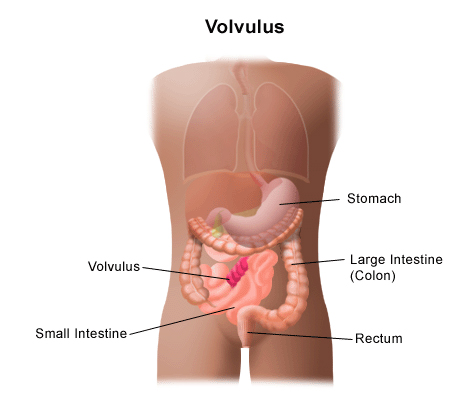

A child with malrotation may experience a twisting of the intestine known as a volvulus. This will cause an obstruction, preventing food to move through the intestine. The blood supply to the twisted part of the intestine can be cut off, which can lead to the death of that segment of the intestine.

Ladd’s bands, formed between the cecum and the intestinal wall, can also create a blockage in the duodenum as a result of malrotation, preventing food from being digested.

A child can become dehydrated quickly when intestinal blockage occurs. The younger the child the more quickly dehydration occurs.

What are the symptoms of malrotation and volvulus?

The following are the most common symptoms of malrotation and volvulus. However, each person may person symptoms differently. When the intestine becomes twisted or obstructed, the symptoms may include:

- Vomiting bile (green digestive fluid)

- Drawing up the legs

- Abdominal pain

- Swollen abdomen

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Rectal bleeding

- Failure to thrive

- Rapid heart rate

- Rapid breathing

- Bloody stools.

The symptoms of malrotation and volvulus may look like other conditions or medical problems. Consult your child’s doctor for a diagnosis.

How is malrotation and volvulus diagnosed?

In addition to a physical exam and medical history, diagnostic procedures for malrotation and volvulus may include various imaging studies (tests that show pictures of the inside of the body). These are done to evaluate the position of the intestine, and whether it is twisted or blocked.

These tests may include:

- Blood tests. Tests to check electrolytes.

- Stool guaiac. A test to detect blood in stool samples. Learn more about stool tests.

- Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan). A diagnostic imaging procedure using a combination of X-rays and computer technology to produce horizontal, or axial, images (often called slices) of the body. A CT scan shows detailed images of any part of the body, including the bones, muscles, fat, and organs. CT scans are more detailed than general X-rays.

- Abdominal X-ray. A diagnostic test that may show intestinal obstructions.

- Barium swallow/upper GI test. An X-ray procedure done to examine the intestine for abnormalities. A fluid called barium (a metallic, chemical, chalky, liquid used to coat the inside of organs so that they will show up on an X-ray) is swallowed. An X-ray of the abdomen may show an abnormal location for the small intestine, obstructions (blockages), and other problems. The upper GI series generally looks at the small intestine while the barium enema looks at the large intestine.

- Barium enema. An X-ray procedure done to examine the intestine for abnormalities. A fluid called barium (a metallic, chemical, chalky, liquid used to coat the inside of organs so that they will show up on an X-ray) is given into the rectum as an enema. An X-ray of the abdomen may show that the large intestine is not in the normal location.

Learn more about blood tests and imaging studies at CHOC.

What is the treatment for malrotation and volvulus?

Specific treatment for malrotation and volvulus will be determined by your child’s doctor based on the following:

- The extent of the problem

- Your child’s age, overall health and medical history

- The opinion of the surgeon and other doctors involved in your child’s care

- Expectations for the course of the problem.

Malrotation without volvulus is often repaired surgically with the Ladd’s procedure.

Malrotation of the intestines is not usually evident until the intestine becomes twisted (volvulus) or obstructed by Ladd’s bands and symptoms are present. A volvulus is considered a life-threatening problem, because the intestine can die when it is twisted and does not have adequate blood supply.

Children may be started on IV (intravenous) fluids to prevent dehydration and antibiotics to prevent infection. A tube called a nasogastric (or NG) tube may be guided from the nose, through the throat and esophagus, to the stomach to prevent gas buildup in the stomach.

A volvulus is usually surgically repaired as soon as possible. The intestine is untwisted and checked for damage. Ideally, the circulation to the intestine will be restored after it is unwound, and it will turn pink.

If the intestine is healthy, it is replaced in the abdomen. Since the appendix is located in a different area than usual, it would be difficult to diagnose appendicitis in the future. An appendectomy (surgical removal of the appendix) is also usually done.

If the blood supply to the intestine is in question, the intestine may be untwisted and placed back into the abdomen. Another operation will be done in 24 to 48 hours to check the health of the intestine. If it appears the intestine has been damaged, the injured section may be removed.

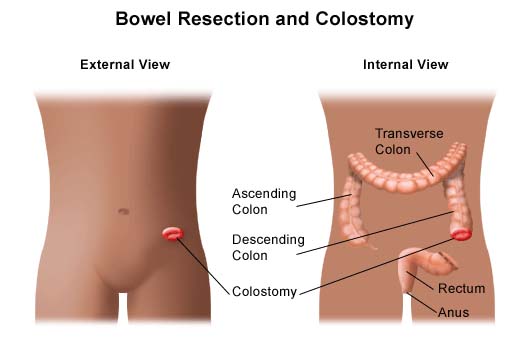

If the injured section of intestine is large, a significant amount of intestine may be removed. In this case, the parts of the intestine that remain after the damaged section is removed cannot be attached to each other surgically. A colostomy may be done so that the digestive process can continue. With a colostomy, the two remaining healthy ends of intestine are brought through openings in the abdomen. Stool will pass through the opening (called a stoma) and then into a collection bag. The colostomy may be temporary or permanent, depending on the amount of intestine that needed to be removed.

What is the long-term outlook for a child with malrotation or a child with malrotation and volvulus?

What is the long-term outlook for a child with malrotation or a child with malrotation and volvulus?

The majority of children with malrotation and symptoms that required surgery do not have long-term problems. They do tend be at higher risk for symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux.

The majority of children with malrotation who experienced a volvulus do not have long-term problems if the volvulus was repaired promptly and there was no intestinal damage.

Children with intestinal injury who had a damaged part removed may have long-term problems. When a large portion of the intestine is removed, the digestive process can be affected because nutrients and fluids are absorbed from food in the small intestine. Removing a large segment of the intestine can prevent a child from getting enough nutrients and fluids.