What is an atrioventricular canal defect?

Atrioventricular canal (AV canal or AVC) defect is a congenital heart defect. That means it is present at birth. Other terms used to describe this defect are endocardial cushion defect and atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD).

Atrioventricular canal (AV canal or AVC) defect is a congenital heart defect. That means it is present at birth. Other terms used to describe this defect are endocardial cushion defect and atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD).

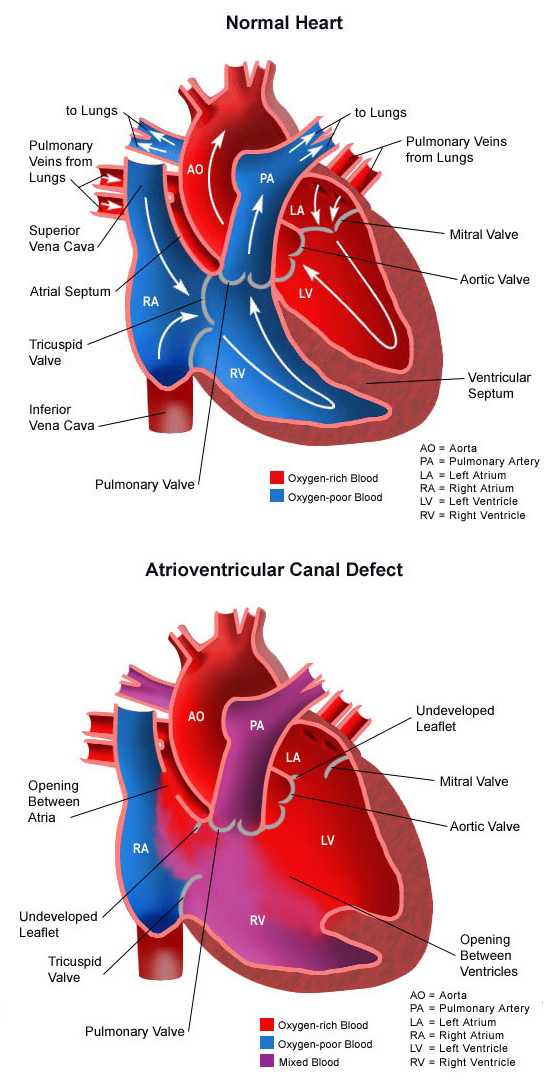

As the fetus is growing, something occurs to affect heart development during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy, and certain areas of the heart do not form properly. Normally, oxygen-poor (blue) blood returns to the right atrium from the body, travels to the right ventricle, then is pumped into the lungs where it receives oxygen. Oxygen-rich (red) blood returns to the left atrium from the lungs, passes into the left ventricle, and then is pumped out to the body through the aorta. This, however, is not the case with an AV canal defect. This complex heart problem involves several abnormalities of structures inside the heart, including:

- Atrial septal defect (ASD). An opening in the wall (septum) between the two upper collecting chambers of the heart, known as the right and left atria. An atrial septal defect allows oxygen-rich (red) blood to pass from the left atrium, through the abnormal opening in the septum (the wall) between the two atria, and then mix with oxygen-poor (blue) blood in the right atrium. Learn more about atrial septal defect.

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD). An opening in the wall (septum) between the two lower pumping chambers of the heart, known as the right and left ventricles. A ventricular septal defect allows oxygen-rich (red) blood to pass from the left ventricle, through the opening in the septum (the wall) between the two ventricles, and then mix with oxygen-poor (blue) blood in the right ventricle. Learn more about ventricular septal defect.

- Improperly formed mitral and/or tricuspid valves. The valves that separate the upper heart chambers (atria) from the lower heart chambers (ventricles) are improperly formed. Specifically, there is an abnormality in the left-sided valve (the mitral valve). It has three cusps, rather than the two cusps that normally form the valve. One of the normal cusps is divided into two cusps. This is called a cleft (or a cut in the mitral valve). Abnormalities of the mitral or tricuspid valves allow blood that should be moving forward from the ventricle into either the pulmonary artery or the aorta to instead flow backward into the atria. This leakage of the mitral or tricuspid valves is called regurgitation.

Atrioventricular canal defects occur in a small percentage of congenital heart disease cases and are more common in infants with Down syndrome.

What causes atrioventricular canal defect?

The heart forms during the first 8 weeks of fetal development. It begins as a hollow tube, then partitions within the tube develop that eventually become the septa (or walls) dividing the right side of the heart from the left. Atrial and ventricular septal defects occur when the partitioning process does not occur completely, leaving openings in the atrial and ventricular septum. The valves that separate the upper and lower heart chambers are being formed in the latter portion of this period, and they too do not develop properly.

Genetic influences may contribute to the development of atrioventricular canal defect.

- Half of all children born with Down syndrome have congenital heart disease (CHD). Close to half of these cases have an AV canal defect. Down syndrome is caused by the presence of three #21 chromosomes in the cells of the body, rather than the usual pair #21 chromosomes.

- Similarly, about one-third of all children born with AV canal defect also have Down syndrome.

- Mothers with an AV canal defect are at increased risk of giving birth to a child with the disease.

Other chromosome abnormalities (in addition to Down syndrome) are linked to this condition. Maternal age can have an effect on the prevalence of the defect.

Why is atrioventricular canal defect a concern?

If not treated, this heart defect can cause lung disease from too much blood flow going to the lungs. When blood passes through both the ASD and VSD from the left side of the heart to the right side, then a larger volume of blood than normal is pumped to the lungs. This extra volume of blood is also under high pressure. This blood then passes through the pulmonary artery into the lungs, causing higher volume than normal and higher pressure than normal in the blood vessels in the lungs.

The lungs are able to cope with this extra volume of blood at high pressure for a while. (These children breathe at a faster rate than normal because their lungs have a lot of extra blood at high pressure compared to children without this condition.) After a while, however, the blood vessels in the lungs become damaged by this extra volume of blood at high pressure. The blood vessels in the lungs get thicker. Those changes are reversible at first. With time, however, these changes in the lungs become irreversible.

As the arteries in the lungs get thicker, the flow of blood from the left side of the heart to the right side and on to the lungs will reduce. Blood flow within the heart goes from areas where the pressure is high to areas where the pressure is low. If the septal defects are not repaired, and lung disease begins to occur, pressure in the right side of the heart will eventually exceed pressure in the left. In this instance, it will be easier for oxygen-poor (blue) blood to flow from the right side of the heart, through the ASD and VSD, into the left side of the heart, and on to the body. When this happens, the body does not receive enough oxygen in the bloodstream to meet its needs, and causes a blue coloring to the skin, lips and nailbeds. This condition (called Eisenmeinger syndrome) is extremely rare because care is taken to repair AV canal defect before lung disease occurs.

Bacteria in the bloodstream can occasionally infect the abnormal valves in the heart (the abnormal mitral and tricuspid valves associated with AV canal defect), causing a serious illness known as bacterial endocarditis.

What are the symptoms of an atrioventricular canal defect?

The size of the septal openings will affect the type of symptoms noted, the severity of symptoms and the age at which they first occur. The larger the openings, the greater the amount of blood that passes through from the left side of the heart to the right and overloads the right heart and the lungs.

Symptoms frequently start in infancy. The following are the most common symptoms of AV canal defect. Each child may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include:

- Fatigue

- Sweating

- Pale skin

- Cool skin

- Rapid breathing

- Heavy breathing

- Rapid heart rate

- Congested breathing

- Disinterest in feeding or tiring while feeding

- Poor weight gain.

Over time, as the pressure in the lungs increases, blood within the heart will “shunt” through the septal openings from the heart to the left. This allows oxygen-poor (blue) blood to reach the body and cyanosis will be noted. Cyanosis gives a blue color to the lips, nailbeds and skin. This is very rare in the United States because care is taken to repair this type of congenital heart defect before lung disease occurs. The symptoms of AV canal defect may resemble other medical conditions or heart problems.

How is AV canal defect diagnosed?

Typically, a child’s pediatrician detects a heart murmur during a physical examination and refers the child to a pediatric cardiologist for a diagnosis. In this case, a heart murmur is a noise caused by the turbulence of blood flowing through the opening from the left side of the heart to the right. The child may have other symptoms that help with the diagnosis.

At CHOC, our pediatric cardiologists specialize in the diagnosis and medical management of congenital heart defects, as well as heart problems that may develop later in childhood. In order to diagnose the defect, the cardiologist will perform a physical examination, listen to the heart and lungs and look for other symptoms that may indicate AV canal defect. The location within the chest that the murmur is heard best, as well as the loudness and quality of the murmur (harsh, blowing, etc.) gives the cardiologist an initial idea of which heart problem the child may have. Diagnostic testing for congenital heart disease varies by the child’s age and current health conditions. Some tests that may be recommended include:

What is the treatment for atrioventricular canal defect?

Specific treatment for atrioventricular canal defect is determined by the child’s healthcare team based on:

- The child’s age, overall health and medical history

- Extent of the disease

- The child’s tolerance for specific medications, procedures or therapies

- Expectations for the course of the disease

- The family’s opinion or preference.

AV canal defect is treated with surgery. Medications may be necessary until the operation is done. Treatment may include:

Medical management. Many children will need to take medications to help the heart and lungs work better due to strain from the extra blood passing through the septal defects. Medications that may be prescribed include the following:

- Diuretics. The body’s water balance can be affected when the heart is not working as well as it could. These medications help the kidneys remove excess fluid from the body.

- ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors. Dilates the blood vessels, making it easier for the heart to pump blood forward into the body.

- Digoxin. Helps strengthen the heart muscle, enabling it to pump more efficiently.

Adequate nutrition. Infants may become tired when feeding, and may not be able to eat enough to gain weight. Options that can be used to ensure a baby will have adequate nutrition include:

- High-calorie formula or breast milk. Special nutritional supplements may be added to formula or pumped breast milk that increase the number of calories in each ounce, thereby allowing the baby to drink less and still consume enough calories to grow properly.

- Supplemental tube feedings. Feedings given through a small, flexible tube that passes through the nose, down the esophagus and into the stomach, can either supplement or take the place of bottle feedings. Infants who can drink part of their bottle, but not all, may be fed the remainder through the feeding tube. Infants who are too tired to bottle feed may receive their formula or breast milk through the feeding tube alone.

Infection control. Children with certain heart defects are at risk for developing an infection of the valves of the heart known as bacterial endocarditis. It is important for parents to inform all medical personnel of their child’s atrioventricular canal defect so they may decide if antibiotics are necessary before any major procedure.

Surgical repair. The goal is to close the septal openings and repair the valves before the lungs become damaged from too much blood flow and pressure. The child’s cardiologist will recommend when the repair should be done. The operative methods used to repair AC canal have improved greatly in the past decade, and the operation has a high likelihood of success. Most children undergo surgery by the age of 6 months, and the procedure is done under general anesthesia. Children with Down syndrome may develop lung problems earlier than other children, and may need to have surgical repair at an earlier age.

At surgery, the ventricular septal defect and atrial septal defect are closed with a synthetic patch. The valve repair technique consists of converting the abnormal three-leaflet mitral valve into a two-leaflet mitral valve. This is done by suturing the cleft (the cut in the valve leaflets) to recreate a two-leaflet (two-cusp) mitral valve.

Learn more about heart surgery at CHOC.

What is the long-term outlook after AV canal surgical repair?

Many children who have had an AV canal defect repair will live active, healthy lives. Activity levels, appetite and growth will eventually return to normal in most children. The child’s cardiologist may recommend that antibiotics be given to prevent bacterial endocarditis for a specific time period after discharge from the hospital.

Some children will still have some degree of mitral or tricuspid valve abnormality after AV canal repair surgery. This may require another operation in the future to repair the leaky or blocked valve(s). Ongoing periodic visits with the child’s cardiologist are crucial to keeping the child as healthy as possible.

Families should consult with the child’s physician regarding their child’s specific long-term outlook.